Below is an excerpt from Clay Bodies. [Cross posted on Poetry, Prose & Pottery]

Above: A portrait attributed to Mary Ellen Keeler neé Simpson, Rufus Keeler’s mom.

2023. Riverside, California.

Some family stories lodge in the brain like a burr. What part of the story is fiction and which is fact? What makes them true is the extent to which they are repeated, but like that telephone game, the more they’re repeated, the more they change.

Who was Great Grandpa Rufus’ mother?

That has been a persistent question for me as I have been researching. Not only have I wanted definitively to know what her name was, but also: Who was she? What was she like? What did she like? Where did she come from?

From the website behindthename.com, the name Mary stems from the ancient Egyptian word mry meaning beloved, or possibly mr, meaning love, later translated into Hebrew as Myriam, Moses’ sister, then Maria, and finally anglicized to Mary. The name Ellen is the Medieval English derivative of the Greek Helen, meaning torch, or possibly even moon. Helen was the daughter of Zeus and Leda. Together, Mary Ellen means something akin to beloved light. The two stories—Moses and Miriam and Zeus and Leda—rub up against one another in my kin, .

I’ve taken my clues as I can find them, and they all lead back to one name, but three different people, all named Mary Ellen.

All three play crucial roles in this story but only one is Rufus’ mother, and another Rufus’ wife. The third, no less important, is more of a walk-on, but still—she is an important figure.

It doesn’t help matters that Rufus’ mother is an enigma. Nobody talked about her. There were whispers. Did she run off? What happened to her?

How to peel apart the different Mary Ellens?

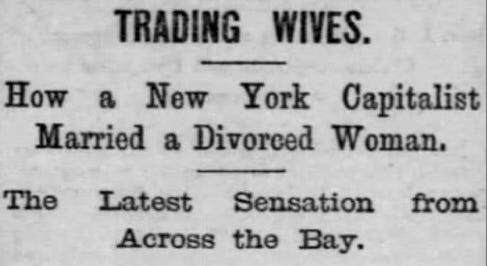

To answer this, I turn to ancestry.com and dig through census data, city directories, marriage records, but instead of answering my questions, they dredge up new clues, like this scandalous piece alleging the “trading of wives.”

The headline reads, “How a New York Capitalist Married a Divorced Woman.”

It appears in the San Francisco Examiner, Monday November 29, 1886, in which it is called “the latest sensation from across the bay” and a “compound complex marriage and divorce arrangement,” the article tells of two men, Charles T. Hickok and B. Keller (sic), their friendship, and the dissolution and subsequent reconstitution of their marriages.

Some true stories have the ring of fiction in the retelling, and so it is with the entanglement of the Hickoks and Keelers and Bleuels and Simpsons, but I believe I’ve unearthed enough facts to corroborate at least a basic outline of the story, in spite of their misspelling of our family name.

Rochester, New York, was a burgeoning modern city, and 1850 was a census year. Charles Theodore Hickok and Bradley Burr Keeler (or Burr Bradley, as he seemed to prefer, B.B. for short) — perhaps new each other as children, both living in Ward 4 during the census taking. Mary Ellen Bleuel’s family lived in Ward 6 in 1860 and then Ward 13 in 1870.

At the time of the census, B.B.’s father, Rufus E., is officially noted as a “farmer” on the census, but to my reading, and based on other information I’ve gleaned, it may and likely does read, “tanner.” He worked in leather, becoming a prominent local businessman and real estate investor before he is the first named Fire Captain, and then later he will spend a year as Mayor of Rochester. At age sixteen, B.B. enrolled in the University of Rochester and studied on the Bachelor of Science track for two years before enlisting in the Union Navy as a landsman on several Naval gunboats for another year. After his discharge 1863, he returned to Rochester and working for his brother-in-law in the tobacco business, and in February of 1875 B.B. marries a hometown girl named Mary Ellen Bleuel, daughter of a Swiss carpenter and French mother, in a Manhattan courthouse wedding. For the first few months of marriage, they live in the Keeler family home on S. St. Paul in Rochester along with B.B.’s mother along with sister Natalie and brother Theodore Valleau “T.V.” and wife Ruby.

Upon his father’s death, and concurrent with his marriage, the newlyweds set off for California in search of the land of milk and honey as written by the eminent journalist and non-fiction author, Charles Nordhoff, grandfather of the other eminent author Charles Nordhoff who authored the classic Mutiny on the Bounty. The elder Nordhoff, author of the railroad-sponsored travel guide, “California: For Health, Pleasure, and Residence,” could be said was almost singlehandedly responsible for the influx of settlers to the west coast, save for the 49ers who had settled in the Gold Rush area. Nordhoff’s depiction of scenic California enticed cold Northerners to make their way to the more temperate California coastline

By now the Bleuel family has relocated to Carpinteria, California, and they are farming. The newlyweds B.B. and Mary Ellen follow. B.B. buys farmland too, and further, he shares title with his wife—an unusual maneuver for the day. The census records note the Keelers, while in Carpinteria, had a Chinese servant named Foo. The next year, B.B. returns to Rochester to retrieve T.V. and Ruby via steamship, and, afterwards, both Keeler households move to Santa Barbara where T.V. opens a furniture shop.

But then a curious thing happens. Within five years, the furniture store goes belly up and T.V. and Ruby move back to Rochester. A news item in the Santa Barbara Daily Press writes,

“Some people who are prone to say mean things intimate sometimes that Mr. Keeler has done more for the town than the town ever did for him, but of course such people are slanderers, in a certain sense. We have Mr. Keeler’s own word for it that he will return here in spirit just as soon as he is killed by lightning, and will have a pleasant word to say to Col. Hollister and Uncle Warren Chase.”

Chase, by the way, was the editor of the newspaper, and Hollister financed the paper, among other ventures.

According to census records, B.B. was by turns a bookkeeper, merchant, farmer, contractor, speculator, and capitalist. Always trying to get ahead, B.B. makes regular trips to Mexico, begins a coconut oil extraction business.

In March of 1882, B.B. makes a land purchase in Santa Barbara that includes a claim to oil, and he is now the vice president of the Santa Barbara Oil Company. During this period, he sells the farm and has gone all-in for commodities - oil, and now a gold mine.

Also, in 1882, he became two-tenths owner of the William Arthur Mines, a goldmine.

In Marysville.

In a parallel story, Charles’ father Benjamin Eldridge Hickok has been running a boarding house that holds thirty-plus other people including women and teenagers, many of whom are young immigrants who either work as laborers or presumably hold positions within the boarding house itself. Charles would have been seven at the time of the 1850 census, the same age as B.B.’s older brother T.V., so it is my best guess that Charles knew B.B. through T.V., although this is pure conjecture. Maybe they played together at school, or on the street; maybe they knew nothing of each other until much later, bonding over a shared hometown finding themselves in a new shared city in a faraway state called California.

Forty miles north of Sacramento is Marysville, the Yuba County seat. An entryway sign reads, “Gateway to the Gold Fields.” Established midway through the 19th century, it is situated in the heart of Gold Country in the vicinity of Sutter’s Mill where the ‘49ers migrated to make their fortunes during the Gold Rush and named for Mary Murphy, one of the surviving members of the Donner Party.

Around the time of the city’s founding, while still in his teens, Charles and his family move to Marysville, where his father buys another motel. Beyond motel keeping, the Hickoks venture into flour milling, purchasing the Golden Rule Flour Mill and move themselves to Oakland.

Now, some might call this a digression, but I’d like to take a moment to tell you a little bit about the Hickoks of Oroville, mostly as a cautionary tale for those of us doing genealogical research.

I’ve been reading a lot about flour.

The (possibly unrelated?) mystery that I’ve been trying to solve for months now is this: Who are the Hickoks of Oroville? Specifically, are they related to the Hickoks of Marysville, a mere 30 miles apart?

In both Marysville and Oroville there is a flour mill.

Both flour mills are owned by men named Charles Hickok.

Same, same?

Not so fast.

One, I discovered, is the afore-mentioned Charles T. who owns and operates the Golden Rule with his father. The other, I learn, is Charles E., who, with his father, owns and operates the Oroville Flour Mill.

It would seem like a logical leap to think that two men with nearly identical names in the same industry towns apart might be related? Maybe?

There’s a lovely obituary for younger Charles Hickock in San Francisco in 1913. Ultimately, he left the flour industry behind and became Water Superintendent for Oroville Water, Light and Power Company.

The beauty of ancestry.com is its searchability. I’ve found both family lines, and in each of them gone back generations to see where they may intersect. I’ve found other family trees that include Charles Hickoks, Benjamin Hickoks, and so on.

If there’s a family connection, I haven’t found it yet.

Meanwhile, back in Marysville—

James M. Simpson, a second generation Scottish immigrant, left Illinois for California with his wife Margaret, an Irish immigrant, and their young son. Along their journey, they stop over in Wisconsin where they have a daughter and another son. Once in Marysville, the couple will have one more daughter along with three more sons.

At first, James operates a cattle ranch, then a ferry across the Yuba River, and finally a bridge which —in an updated form—still stands today on Simpson’s Lane.

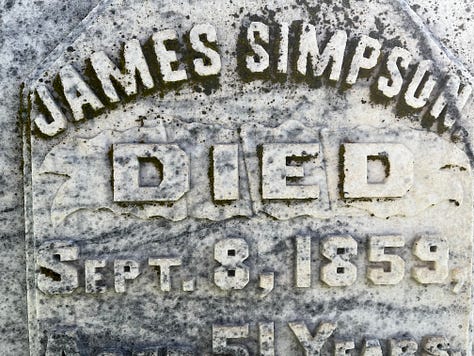

The National Democrat on September 8, 1959, tells the story of James Simpson’s death in a revenge killing, not too far afield from what you might expect from an old Western film. Picture the Landis Ranch in Linda, a short distance from Marysville, and a crowd of cowboys forming. One is tossing out accusations, “You killed my brother!” Soon guns are drawn and bullets are flying. Was James responsible? I don’t know. What I do know is that he left his wife and family alone during a period of time where she, Margaret Fitzgerald Simpson, had to petition the court for custody of her own children, and for the family business—namely, the ferry.

The first mention of Simpson’s Ferry I can find. It appears in the Marysville Appeal on April 30, 1860. “Ferry Rope Broke,” begins the news article.

The boat was empty at the time.

It had just ferried across a train of mules.

A horse and buggy were waiting their turn to cross the Yuba River.

The boat floated a ways before it was secured, and I wonder about the chase that ensued, how many men did it take to recapture the wayward ferry? How did they return it to its point of origin?

What could all of this be a metaphor for?

Sometimes things get away from us.

Mary Ellen Simpson is eleven years old when her father dies. Within ten years, her mother Margaret would remarry. The following year, 1870, Mary, too, would marry, beginning her new life at the age of 22 with husband Charles T. Hickok, but in another two years Mary’s mother would be gone.

In the year 1878, Mary Ellen Hickok neé Simpson gives birth to Charles P.

Then, in 1881, she is pregnant again, this time with a girl. Sadly, the child dies.

Here is where the two women's stories cross, like an intricate cat’s cradle passed from hand to hand. It’s taken some untangling but I believe the following to be true.

Cue the wife-swapping headlines.

The Marysville Appeal writes, on May 28, 1885:

“Trading Off.—The following, which we clip from the Examiner, is of local interest here, by reason of one [of] the families having once been residents of this place: ‘An exceeding lovely case of wife swapping occurred in Oakland within the past year, but has just leaked out… The parties to the ‘swap’ are Mr. and Mrs. Keeler and Mr. and Mrs. Hickok, the latter a son of the proprietor of the Golden Rule Flouring Mill…. Mr. Keeler felt a growing infatuation with the wife of Mr. Hickok, which by the appearance of things, was reciprocated. By a singular coincidence Mrs. Keeler was afflicted by an uncontrollable passion of love for Mr. Hickok, and reciprocity to a degree equal to that in the former case developed. All the parties were aware of the changes of heart… The matter was arbitrated by the four, and finally a mutual agreement was arrived at. The husbands were to change wive, and the wives were to change husbands. The parties moved to San Mateo, where were duly divorced, and Mr. Hickok marched off triumphantly with Mrs. Keeler, while Mr. Keeler expressed himself content with the possession of Mrs. Hickok.”

A later article in the San Francisco Examiner confirms these details:

“I cannot imagine why the newspapers want to know anything about my private business,” he said. “My former wife deserted me and I got a divorce from her in the usual form… Yes, my ex-wife married Mr. Keeler and I am sorry that I ever saw him.”

And so the newly-minted Mrs. Keeler neé Simpson and the now-divorced Mrs. Keeler neé Bleuel go their separate ways.

It was further perpetuated by reprinting in several newspapers from San Francisco to Santa Barbara. This, from the Marysville Daily Appeal, taken from the San Francisco Examiner:

“Trading Off.—An exceedingly novel case of wife swapping occurred in Oakland within the past year, but has just leaked out. The parties concerned are of reputable standing in the community and possessed of considerable means.…”

As the story goes, the two couples were taken to socializing together, one being Mr. and Mrs. Hickok and the other being Mr. and Mrs. Keeler.

The article goes on to say that B.B. worked for The Golden Rule, and that that was how the two couples met, though I can find no confirmation. According to the article, both of the Mrs. — Mary E. Keeler and Mary E. Hickok — were purportedly granted a divorce, one supposedly for desertion of her husband and the other for reported mistreatment by husband. Research on divorce in the Victorian era places that luxury squarely in the realm of the affluent, or at minimum desertion had become a practice of couples who sought divorce and needed a valid reason the courts could hang their hat on. The article concludes that the two couples’ situations were settled amicably, with each content with the other’s spouse.

And they all lived… happily? But not for long.

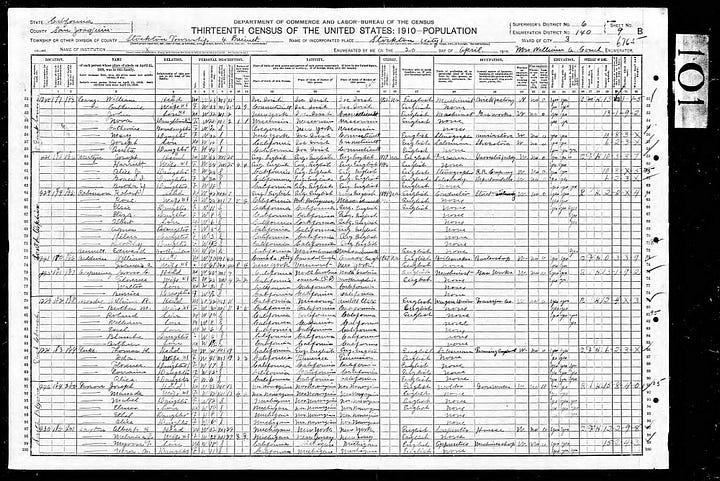

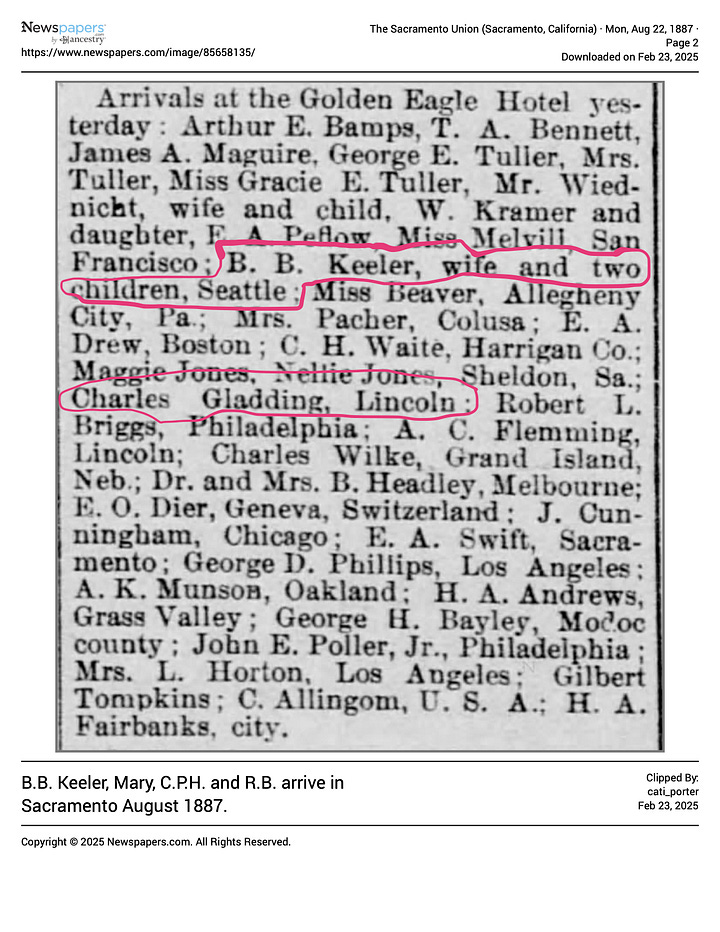

By February of 1885, B.B. and the second Mary E., neé Hickok neé Simpson, were married in Sacramento then made off for Bellingham, Washington, where, by October, she had given birth to a son—my great-grandfather Rufus. If you do the math, either the baby was premature, or she was already pregnant, which would have added another layer of scandal.

The article further claims that Charles T. and Mrs. Mary E. neé Keeler neé Bleuel did marry, but there is no marriage record, and further, voter, census, and newspaper records continue to refer to her as Mrs. B.B. Keeler for the remainder of her life. Articles reference Mrs. B.B. Keeler’s gowns and bathing costumes, apparently newsworthy occasions. Another hiccup in determining which of the Mary E.’s had mothered Rufus. And worse, Mary Ellen Keeler neé Bleuel often went by Marion.

After the divorce scandal, or maybe to get away from it, Charles T. relocated to Portland, Oregon, where again he became a hotel keeper. At first blush it appeared that he never did in fact remarry, but curiously the death certificate listed him as married. Was this a mistake? Could this have been Mary E. neé Bleuel? But no. A quick search of marriage records shows he did, at long last, remarry—about ten years before his death in 1912, to a woman named Catherine Hart.

Meanwhile, B.B. and Mary E. neé Simpson, were living happily in Washington State. Eventually they settle in San Francisco where my great-grandfather is raised alongside his half-brother Charles P.

But happiness isn’t meant to last.

In 1896, Mary E. neé Simpson develops a fatal case of spinal congestion, now commonly known as meningitis, at the age of 48. At the time of her death, the couple was living at 933 Haight Street in San Francisco, just outside of the now-famed Haight-Ashbury neighborhood. The widower B.B., son Rufus, and stepson Charles, would live together as a family unit until the older brother went to work for the Panama Canal.

Rufus, would in time, marry his own Mary Ellen.

This is supposed to be a book about great men.

Still, I keep coming back to the women.

***

Excerpted from a work in progress, Clay Bodies: The Brief Lives and Lasting Legacies of Rufus B. Keeler and Brad Keeler, Father and Son Ceramicists, and copyright the author Cati Porter. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part without permission of the author except as embodied in critical articles or reviews.

https://www.copyright.gov/help/faq/faq-fairuse.html

Baby Rufus arrives with dad B.B., mom Mary, and older brother Charles.

Baby Rufus arrives with dad B.B., mom Mary, and older brother Charles. The Golden Eagle Hotel in Sacramento. Picture found on Calisphere.

The Golden Eagle Hotel in Sacramento. Picture found on Calisphere. Detail of scroll work with lichen/moss.

Detail of scroll work with lichen/moss. Detail of the top of the M in Simpson.

Detail of the top of the M in Simpson. Detail of the engraving on the monument.

Detail of the engraving on the monument. Foot of the monument with silk flowers.

Foot of the monument with silk flowers. Me with the monument.

Me with the monument. Catherine Porter

Catherine Porter